If you’ve ever seen The Perfect Storm, you’ll know that quite a lot of things go wrong in it.

The Perfect Storm is a film about fishing, starring George Clooney, Mark Wahlberg and quite a few other people you know.

At one point Wahlberg is bitten by a shark. A bit later John C Reilly is hooked and dragged into the sea. And then the bad weather arrives.

The bad weather in The Perfect Storm is, as you’d imagine, quite a few steps beyond ‘persistent drizzle’.

Clooney and his men have a jolly good stab at coping with it, but the odds are very much against them and pretty much everything anyone tries to do for the greater good looks like suicide.

Clooney has to climb a 20ft clanking gantry that flaps up and down, throwing him about; helicopters try and refuel in mid-air – the whole thing is absolutely bloody horrifying.

If the weather in The Perfect Storm provides a lesson, it’s that sometimes a whole bunch of stuff goes against you to create a situation that is quite simply a bit too much for you and there’s really not that much you can do about it.

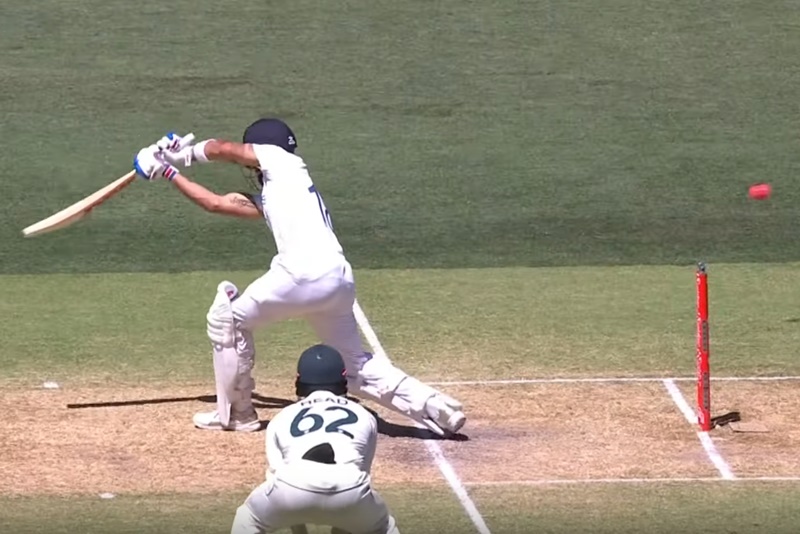

All out for 36

All out for 36 is not a good innings. We can probably agree on that. It is, however, a one-dimensional collapse.

What India can take from being bowled out for 36 is that while they clearly didn’t do much right, they also didn’t do an enormous amount wrong – because they simply didn’t have time.

The really, truly godawful low scores are almost always sufficiently freakish that they cannot be wholly damning in isolation. They’re not to be ignored, but they tend to speak only of narrow failings.

The England team of the 1990s? Now that was a side that could collapse. That was a side of three-dimensional collapsibility that proved its worth against all opponents in all conditions.

1990s England could get bowled out for a double digit score, but 1990s England could also put on 200 for the first wicket and get bowled out for 200.

1990s England could spend a whole day collapsing while failing to score runs or they could get bowled out in a session while scoring at five an over.

1990s England could do it all.

What have 2020 India done?

2020 India have done very little. 2020 India have lost wickets to the two most accurate bowlers in the world with the new ball on a challenging pitch.

That’s it. They didn’t really have time to show us anything else. They didn’t even get the chance to play too badly because every time they made a mistake, the batsman was dismissed. Wavell Hinds was once dropped twice on his way to a duck. Now that’s playing badly.

India’s was never going to be a good innings, but sometimes things really don’t pan out for you and a bad innings ends up worse.

Had a couple of chances not gone straight to hand or had the ball beaten the bat instead of finding the edge, maybe they’d have managed a relatively normal score without the batsmen playing any better.

Because maybe then someone or other would have got to face a bowler who wasn’t Pat Cummins or Josh Hazlewood. Maybe they’d at least have got to face a slightly more tired Pat Cummins or Josh Hazlewood. Maybe they’d have got to face a slightly more tired Pat Cummins or Josh Hazlewood with an older ball. All these things make a difference.

It’s pretty obvious that the India side who were bowled out for 36 were never likely to make 400. But look at it this way: they only really had time to do one thing wrong.

We also send all of this stuff out by email. You can sign up here.

At least it shows us that England’s batting efforts in the Ashes were relatively good compared to this one-dimensional India side.

There weren’t even any particularly bad shots like Haddin’s in South Africa, mostly just nicking pretty good balls. I have to say it was thoroughly fun watching it, hard to beat a collapse for pure spectacle.

England in the 90s, the benchmark of crapness, were bowled out for double figures five times. England since 2000, who were often quite good, were bowled out for less than 100 eight times, four per decade.

90s England weren’t desperately more prone to Uber-skittlings than their better regarded successors. Their flaws were more subtle.

I reckon variance of scores is much greater in modern Test cricket generally. And you raise a good point. Perhaps it’s with making a distinction between a “skittling” and a “collapse”? 90s England were seldom skittled but whatever score they were on, as a supporter you were constantly aware they still had the knack for a spectacular collapse.

They were real X-factor collapsers. They could collapse from any position.

Sadly we were denied the sight of 90s England managing a proper pink-ball collapse. Bet they’d have been great at it.

The 90s would have been a less depressing time to support England if more of their collapses had come from a position of 500/4.

This was irritating beyond belief for me.

Coming off an inhumanly busy week, I looked at the scorecard last night and thought, “great. Match well set. Day/Night test match. I’ll just wake up when I no longer feel tired and should at the very least get to see two or three hours of cricket in the morning.”…

…except it was game over by the time I got up around 8:00ish.

Bloody Aussies, always spoiling my fun.

I envy your energy Ged, if I followed that approach I’d have lost my job by now

I didn’t mean to suggest for a moment that they weren’t collapsers. They manifestly were. Just more 180 all out collapsers than especially 60 all out collapsers, which still loses you plenty of games.

And, of course, on the last two occasions where England have been bowled out sub 100 they have gone on to win, which didn’t happen back then.

But enough of England, this is Indias’s day.

There is a line of argument, of course, that day/night, pink-ball test cricket is comparatively tricky for batting, such that teams might expect an innings score to be around 60% of the equivalent score in a regular red-ball test match.

On that basis, India’s score of 36 would be equivalent to…

…no, sorry, my arithmetic is failing me. But perhaps someone more adept at such matters could complete the calculation and let us know if Australia had, by any chance, achieved such an equivalently miserable score within living memory. Gosh, that would be a sight to see, wouldn’t it. But I don’t suppose anyone around here has been so lucky.

India and Australia’s scores would have been:

India 1st Innings: 406

Australia 1st Innings: 318

India 2nd Innings: 60

Australia 2nd Innings: 155/2

I think that is correct, wickets would obviously be the same but I can’t be bothered to list all them out and all of you are not probably interested anyway.

Thanks Chabuddy. Gosh. 60 all out. Has anyone ever seen such a thing?

It’s hard to imagine any side could ever have been bad enough to have been bowled out for 60.

60 would obviously be a worse performance than 36 as run scoring would demonstrably be easier in that scenario.

Collapses are also more common with the new pink ball.

In fact, pink ball Tests are much more predictable than their red ball counterparts. It’s much more difficult to arrest momentum – in either direction – with the painted ball.

That was what was so good about the first Headingley innings last year. Remember Ben Stokes’ shot? Remember the way Jofra Archer got out by ducking under a bouncer but leaving his bat in the way? Remember the fact that Joe Denly top-scored with 12? Remember Rory Burns trying a pull shot and not even clearing the wicket-keeper? Remember Jack Leach being bowled around his legs by a straight one from the world’s best line-and-length bowler?

Headingley was a proper collapse.