If you’re really going to turn the heat up and cook a sauce for quite some time, you need plenty of good stuff in the pan to begin with. If you haven’t, you’ll end up with a bitter-tasting charred sticky goo that’s no good to anyone. England are different gravy.

Our story starts a few years back with plans to play two huge Test series against India, a T20 World Cup and an Ashes series in the space of a few months.

This was something we first spotted in 2018. “Try and imagine how you would switch off and recover if your whole career hinged on making runs or taking wickets in these matches,” we wrote back then – blissfully unaware that a pandemic was about to be thrown into the mix too.

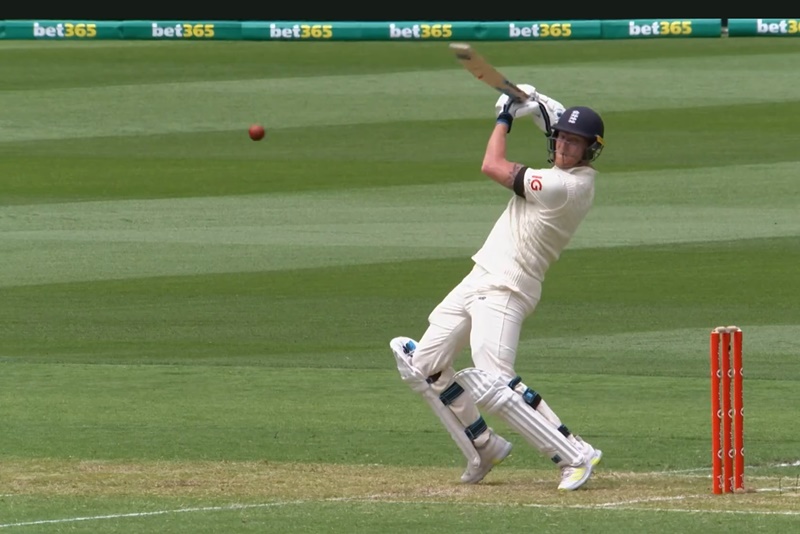

One of England’s fresher players for the 2021/22 Ashes series was Ben Stokes. This was because he hadn’t played quite so much cricket in the lead-up, having sacked off the sport halfway through the year because he simply couldn’t take it any more.

“The demands on our athletes to prepare and play elite sport are relentless in a typical environment, but the ongoing pandemic has acutely compounded this,” said the managing director of England Men’s Cricket, Ashley Giles, back when Stokes made that decision.

“Spending significant amounts of time away from family, with minimal freedoms, is extremely challenging,” continued Giles. “The cumulative effect of operating almost continuously in these environments over the last 16 months has had a major impact on everyone’s wellbeing.”

That was July. The cumulative effect had already taken out England’s most important player before the home series against India, before the T20 World Cup and before the exhausting negotiations about whether to go to Australia or not.

The last of those is the kind of unavoidable extra stress that is routinely thrown into the mix these days. Just a few weeks ago, England’s tourists still didn’t know where they’d be playing the fifth Test.

Cricket all day, every day

In recent times there’s been a lot for England’s players to think about beyond bowling the ball and hitting it, yet the schedule hasn’t exactly flexed to accommodate that.

Stokes has played seven Tests, six one-day internationals and five T20 internationals this year. Unremarkable, except that that’s the “time off because you simply can’t cope with it any more” workload.

Jonny Bairstow – not generally a first choice in the Test team – has played nine Tests, six ODIs and 17 T20Is.

Joe Root, as Test captain, has barely seen a white ball. He has however played 15 Tests.

Simply listing the matches played is hugely misleading though. It’s that non-stop tension between times that is the silent killer – something that only becomes greater when you’re underperforming as a player.

Just ask Jonathan Trott. He described the three weeks “off” ahead of the 2013/14 Ashes as being “pretty intense” as a result of the work he was putting in. Come the tour itself, he committed to even longer hours in the nets, to the extent that he was sometimes still there when Alastair Cook wanted to name the team.

Midway through the 2021 Adelaide Test, we suggested that thanks to all the talk and planning and practice and other fixtures, England as a whole were starting to look a bit cricketed-out. David Gower has always said that the brave thing to do in that situation is to completely step away from the sport. In a game of reflexes, a great pile up of thought, theories and worries really doesn’t help you. By busying yourself with something trivial and unrelated for a while, you allow all of that unhelpful stuff to subside a little and give yourself a better chance of just reacting.

Getting away from cricket is quite a hard thing for an England player to do at the best of times and harder still when there are back-to-back Tests. A whole bunch of virus-induced restrictions don’t exactly help either.

England went the other way anyway. They decided to immediately rewatch all of their Adelaide dismissals and dissect them at great length. This approach meant they successfully magnified all of their existing frailties in time for Melbourne.

We can blame Joe Root and Chris Silverwood for this and for several of their other decisions, but it’s worth pointing out that these two men have been mentally shredded by this unrelenting environment and its unremitting atmosphere too. That’s not an excuse, but it should at least be held in mind to temper the criticism.

The whys

‘Why have England lost the Ashes?’ and ‘Why are England losing so badly?’ aren’t quite the same question.

There is much talk about the standard of England’s first-class cricket and the way it’s set up to diminish the significance of fast bowlers and spinners.

This is a large part of the reason why England have lost the Ashes. A few more four-day games in July and August isn’t really the answer though because the nonsensical pressures that gave rise to the spring-and-autumn first-class schedule in the first place – specifically four formats, five competitions and no time to practise between games – would still remain.

Everyone’s got a least-favourite format they blame for this, but it’s a far more fundamental thing. You may add to the English cricket season but you may never take away – that’s the golden rule. Throw in the sport’s near-invisibility over the last 15 years, an ever-narrowing player pool and a sterile monoculture in the Test setup and you’ve got a pretty unpleasant recipe.

That structure creates not-great players and a not-great England Test team that hasn’t been able to bat in years. That’s how England lost the Ashes.

The insanity of their 2021 schedule multiplied by the insanity of bubble life multiplied by the insanity of trying to make burnt-out mediocre players better by asking them to redouble their efforts is how they got bowled out for 68 by Scott Boland.

If you’re a particularly vindictive person, you can help us continue to cover England’s Test performances by flipping us a coin or buying us a pint each month via Patreon. We probably need something stronger than beer.

Funding or no funding, you can get our articles by email.

Surely the problem is that the ECB is, well, to put it in one word, awful.

It is set up in a way where the primary goal is profit not performance. It’s not a malicious or incompetent thing so much as that they’re running the wrong race.

The BCCI is also set up with profit as it’s primary goal. However in order to break into the top tier of world cricket, they realised that the team would have to perform, home and away.

Maybe the ECB will realise that if they lose their seat at the top table.

So, having brought us all the way back to the 90s in 15 years, how do England get back to being good again?

With no cricket on the TV, players understandably focused on making money in their careers and therefore franchise cricket, will England ever be any good at Tests again? Is this it?

I could write 2021 off as a particularly stupid aberration with lots of extenuating circumstances, but we’re getting on for a generation in which only one good batter has been unearthed and played at a sustained good level.

If the focus really is going to be entirely on limited overs stuff from here on, I might be done with cricket.

Remember the 2015 ashes? This young batch of players were so exciting that year. England cricket burns its players out at a ridiculous rate.

I can’t stop reflecting on the idea that the Hundred is a terrible solution to a number of significant structural problems, in that it a) adds to the schedule and b) creates a new format of cricket that no-one has any real interest in and c) sucks away resources from pre-existing teams and competitions.

It tries to solve the problem of no cricket matches unless you’re paying for Sky/BT and it tries to solve the problem of there being eighteen county teams that all run relatively independently of the national set-up.

I have no third paragraph.

This is the way county cricket has always been run. They try and solve a problem, come up with a solution, then commit to that solution even when it’s been compromised into a shape where it no longer solves anything and in fact creates new problems. Then they come up with new solutions for those and they get compromised. Repeat.

So, at least there aren’t any extra Tests being shoehorned into an already-busy schedule in 2022 then, eh?

I agree with this, but we also need to factor in that if elite sport isn’t mentally challenging, what is it bothering for? That is to say, sport at this level should be tough, and the people capable of doing it only the toughest around.

I’m sure this is already true, so to then completely ruin the mental health of the toughest around takes a special effort. Elite stupidity, you might say. And yes, the workload of matches is part of it. But I can’t help thinking that it’s more to do with how the players are managed than how much cricket, or what type, they play.

The rot started (this time round) with Alastair Cook. Under him, England became progressively more one dimensional, monocultural. He was Graham Gooch’s protégé, and god didn’t it show. And just as with Gooch, he handed back a shell of what he’d been given, a team in absolute tatters.

The trouble with monocultures is that you spend all the effort you have becoming a tough test standard cricketer, and then you’re asked to spend all of that again on fitting in. This is the overload. You cannot switch off because all your escape hatches – friends, relaxation, being you – have been sealed shut.

All of our better captains, from Brearley to Strauss, have understood this implicitly. You, the test match player, must prepare fully for every test match, but how you prepare is up to you. You will be judged on how well you perform, not on how many laps of the pitch you ran, or how many essays you wrote, or how many videos you watched. And especially you will not be judged on conformity to a cultural standard. Just be you, and let the cricket flow.

When Cook left, I hoped Root would take over because I thought he was not that. Maybe the shell of what was left wasn’t capable of being built on. But this mess needs a better approach. We can’t persist with a system in which our best player doesn’t want to play.

It’s weird how the white ball sides – which run parallel to and slightly overlapping the Test side – are run with clear ideas about how they should be formed; absolute commitment to those ideas even when results aren’t good; and an explicit celebration of diversity. Does none of that rub off?

There are a lot of people slagging off ‘the focus on white ball cricket’ as if it’s a zero sum game. It’s true that it can have a negative impact on the Test team in some areas – like Jonny Bairstow’s technique or several players’ workloads – but it’s also true that the England Test team has incredible access to the inner workings of one of the best-run elite sports teams around and it’s even the same sport.

That has to be useful. There is clearly something very different going on with these two setups because we can’t see that the formats are so different that one captain has access to bountiful talent and the other can’t find even a handful of semi-competent batters.

India’s Test team seems to be forever calling up people who haven’t played first-class cricket in 18 months or more and these guys just waltz in and perform.

I’m surprised to hear the word monoculture about England. Wasn’t Bayliss and to a lesser extent smith all about free expression and waving the freak flag?

I have never understood the argument that you can either be good at white ball cricket or at test cricket.

By that measure, players like Rohit Sharma and KL Rahul must be worth their weight in gold. And India appears to have 4 or 5 opening batsmen like that.

The thing is, it wasn’t like this before. We would get the odd decent opener like Akash Chopra or M Vijay (and of course Sehwag but he truly was a once in a generation player) but not 5 at once. That has only happened after T20s became a thing.

Yup. (To all of it. Article and comments so far).

As Ged said.

Just to add, or rather to emphasise, it is worth saying that test cricket is unique in elite sports, in that its format for a touring side requires a three-month playing commitment. Footballers go to a World Cup every now and again, and stay in a hotel for four weeks. Cricketers do that for three times as long, every year, often twice a year.

The key management skill for any project like this is handling the obvious problems this will cause. The squad should have a physio, and a batting coach, and a relaxation specialist. It is critical, at least as important as being able to bat.

There is something slightly tautological about preparation, albeit tautologically useful. That is, the best preparation is that which gets the best result. There is no other useful definition. And anyone who thinks that the same preparation will work for everyone is someone who thinks that all people are the same, i.e. an idiot.

Preparation and relaxation go hand in hand. Find what relaxes a player, and build preparation on top of that. And make it matter. Make the happiness and mental comfort of your players the sine qua non of a tour. The results will flow from this.

In 2010/11 the players, Kevin Pietersen included, had the mental capacity to develop a stupid dance, the sprinkler. This was not a consequence of the performances, it was the other way round.

https://twitter.com/abi_slade/status/1476525829836484609?s=21

Highlight of the series so far.

So many great moments. The dancing app. The ‘naughty’ M&Ms. Marnus trying to break in. Two minutes of gold.

Something something nobody can get him out

The way I see it, white ball cricket taking up your peak summer is not going anywhere. To me, if the ECB are still serious about red ball cricket, they need to take charge of future talent and not just leave it to the system/counties.

They need to identify 25 players aged 18-23 who are willing to prioritise Test cricket and/or are clearly not built for T20 cricket. Use the white ball bounties to Invest in this group over the next 2 years – in addition to playing English county cricket, send them on plenty of Lions tours, get them the best of batting & bowling coaches, send them to spin clinics on the sub-continent, to MRF pace academy or Western Australia pace coaches, get them to play first-class cricket over the winter in India, Pak, NZ, wherever else.

Target to have at least 10 of these players in your Test squad for the summer of 2024.

Also, get a professional to manage this program. We had Rahul Dravid managing our A and Age teams. There’s a reason our backup players just turn up and perform.

This is pretty much what they already do.

Obviously, they don’t. If they did, your team would be better.

A lot to agree with, it seems there are 3 main reasons for our current performance levels:

1) The poor and inadequate state of first class cricket in England – producing sub-standard players

2) The non-existent preparation time for the squad, partly due to the proximity of the T20 world cup and partly due to covid isolation. This mustn’t be allowed to happen again, no warm up matches – then no tour.

3) Extremely poor management, Chris Silverwood isn’t up to the job and sadly Joe Root doesn’t seem to have learnt from previous series.

Essentially all 3 have to be addressed. It’s possible to have a good quality first class game, Australia clearly does, and they have similar pressures of the other formats. Preparation must be an integral part of any tour. Find an inspiring manager – there must be somebody better.

My personal wish would be to separate test match players from other formats as much as possible, e.g. Ben Foakes would be my choice for our test match wicketkeeper / batsman. Those who prioritise the IPL should gradually be phased out where possible. Clearly the top players, like Ben Stokes, are needed across all formats but limit and prioritise their workload.

Great article and comments. Think the central issue is children not playing cricket, not wanting to play cricket, and to a remarkable degree not having heard of cricket. The counties are rightly terrified by this, or they’d never have agreed to the Hundred. But a lot of the reasons put forward for it seem to founder on comparisons with football, which is often as bad or worse yet continues its remorseless dominance.

I’m sure there are great articles on this, comparing the situation in different countries, but I can’t remember reading any. How do New Zealand do it? Surely Rugby Union is at least as dominant over there as football is over here, yet they’ve been steadily improving for decades. Or is cricket the only major summer sport over there? But then even if it is, it used to have that status here.

The ECB gets a lot of stick, but Christ it’s got a difficult job on its hands. Even if it had done massively better in most of the areas for improvement that have been identified, I don’t think the fundamental problem would have been greatly reduced.

New Zealand wont be a great team once kane, southee, boult retire. It’s a more than generational talent.

But this batch of players now were part of a strong age group system. Kiwi players were also asked to develop at test level and there was 4 years of mediocrity. Now the team is strong enough that new players bolt through.

It is our only real summer sport. They only play 8 plunket shield matches a year. The black caps might play a third of these.

We have 6 teams and otago essentially is a non starter.

And we absolutely never ever get a warm up match on any tour.

I don’t have a clue why kiwi cricket is going well actually

I know it’s not the only reason, but anecdotally looking at some of New Zealand’s recent selections it feels like, following Brexit, NZ has replaced England as the country of choice for white South African players looking to avoid the quota system.

Simon Doull says there was some sort of overarching decision to play on better pitches in NZ domestic cricket a few years back. We’re not really sure what form that took.

Thank you. I see what you mean about the golden generation, but there also seems to have been a steady improvement since WWII from awful to largely awful to Hadlee and ten others to alright (but it was still a crisis when they beat England in England) to surprisingly good to consistently good. Must be nice when things go unexpectedly right and you don’t know why. Wonder what it feels like.

It’s not the main problem with England, but it is a problem that preparing pitches which reward mediocre medium pace or mediocre spin has become a really good way of competing for the County Championship.

I wonder if this was an unforeseen consequence of two division county cricket? It meant that counties actually cared about winning, and therefore took advantage of flaws in the system which they’d previously ignored. Would follow that previously the county championship was a sham, of course. Which explains a lot.

Happy new year, everyone. Here’s to 2022 being a heck of a lot better than 2021.

And to you, Ged (and all your various associates), and to you.

Oh my goodness, things must be bad, we’ve had to call up Adam Hollioake to help coach.

Something something the England cricket team is like a soap opera something Hollioakes

Or not, since he now also has been exposed.

They’ll have to give Hick a call at this rate.

We should see this (not just the Ashes, but 2021 as a whole) in context. England have been getting relatively worse at producing good cricketers for a hundred and fifty years. Utterly dominant pre WWI, though getting less so until Barnes insisted on bowling continuously throughout both innings and averaging 16. Unable to beat Australia carrying a 2 to 3 substandard amateurs handicap in the interwar period. Back to competing with the best once they got rid of that handicap post war. Then gradual decline to the point where they couldn’t compete as a semi professional team against professional teams by the nineties. Central contracts, etc., and competitiveness again for quite a while before the declining relative talent level once again revealed further flaws in the system, like the falling water level of a reservoir in a drought bringing to light evidence of a terrible crime committed decades ago.

Are there any more major structural or selection changes that can be made that will postpone the inevitable for a few more decades? Or is this, finally, it?

I didn’t think I had a hangover, but I must do. Happy New Year, all.

Reminds us of that bit in Office Space where Peter says that every day is the worst of his life because the next one is always fractionally worse.

Happy New Year!

Where is the Lord Megachief of Gold announcement?

It’s coming.

KP has something to say regarding this – https://sports.ndtv.com/the-ashes-2021-22/kevin-pietersens-radical-proposal-to-save-test-cricket-in-england-2682820.

Sorry if pasting URL’s is not proper etiqutte.

There’s no link-posting etiquette here, Cordish. You’re good.